Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm, enabling machines to learn and make decisions through trial and error. Recent successes in RL, such as agents that play Atari games, hold conversations, control nuclear fusion plasma and discover new algorithms, have demonstrated its potential for solving complex problems. However, the roots of RL can be traced back to an earlier era, where Donald Michie and his creation MENACE, helped pave the way for machines that could learn.

This blog post explores the design and functioning of MENACE, showcasing it as one of the earliest examples of RL. I’ll also provide a Python implementation of MENACE so you can experiment with it yourself.

MENACE’s genesis

During World War II, even before attending college, Donald Michie worked as a code breaker at Bletchley Park where he collaborated with Alan Turing. During their free time, the two men would play chess and theorize how game playing machines could be built.

After the war, both Turing and Michie, in collaboration with others, came up with algorithms that could play chess. In 1948, Alan Turing and David Champernowne developed Turochamp. Somewhat earlier, Donald Michie, together with Shaun Wylie, had thought up a chess program called Machiavelli. These programs were primarily conceptual and required manual execution of instructions. Turochamp and Machiavelli relied on various heuristics to determine the most advantageous moves, with these heuristics being hard-coded without any learning capability.

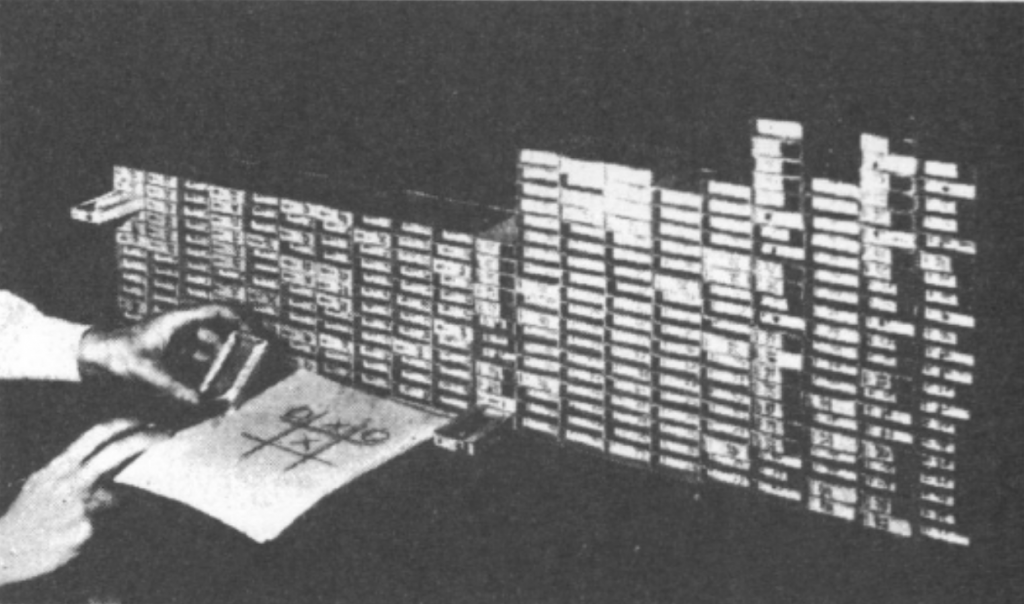

In 1960, Michie wanted to show how a program could actually improve itself by playing many games and learn from its wins and losses. Chess was too complicated because of its many possible game states, so he shifted from chess to the much simpler game of tic-tac-toe (or noughts and crosses as they call it in the UK). Because Michie didn’t have access to a digital computer, he implemented his learning algorithm using matchboxes and colored beads. He called his machine Matchbox Educable Noughts and Crosses Engine, or MENACE.

How MENACE plays and learns

How it’s setup

Each matchbox in MENACE corresponds to a specific configuration of X’s, O’s, and empty squares on the tic-tac-toe game grid. Duplicate arrangements, such as rotations or mirror images of other configurations, are left out. Configurations representing concluded games or positions with only one empty square are also omitted. Furthermore, MENACE always goes first and only its own turns need to be represented. All this results in exactly 304 distinct configurations that MENACE can encounter, so only this many matchboxes are used.

Inside each matchbox, there is a collection of colored beads. Each color represents a move that can be made on a specific square of the game grid.

Matchboxes with arrangements where positions on the grid are already taken don’t contain beads for those occupied positions. Bead colors that represent duplicate moves, resulting from rotating or mirroring the configuration, are also left out.

A matchbox can contain multiple beads of the same color. Initially, the matchbox representing the first move, which corresponds to the empty grid, contains four beads for each color representing a possible move. In this initial move, MENACE has three options: moving in the center, a corner, or a side, resulting in a total of 12 beads. As for its second move, there are at most seven possibilities, and each vacant square has three of the same colored beads associated with it. In the case of MENACE’s third move, there are two beads for each of the at most five possibilities. Similarly, for its fourth move, there is one bead for each of the at most three possibilities.

How it plays

When it’s MENACE’s turn to make a move, one must locate the matchbox that corresponds to the current grid configuration and randomly select a bead from within that matchbox. The chosen bead’s color indicates the square where MENACE makes its move. After each move, the selected matchbox and bead are put aside for later processing. This procedure is repeated for each of MENACE’s turns until a victor emerges or the game ends in a draw.

How it learns

Upon completing a game, MENACE will need to be either ‘punished’ or ‘rewarded’ for its choices based on the outcome. When MENACE loses, the beads representing its moves are simply removed. In the case of a draw, an additional bead of the corresponding color is added to each relevant matchbox. Conversely, if MENACE wins, three extra beads are added for each move it played.

These adjustments in bead quantities directly influence MENACE’s future gameplay. Poor performance reduces the likelihood of MENACE repeating the same gameplay, as the corresponding beads are removed. On the other hand, successful gameplay increases the probability of MENACE following a similar strategy in subsequent games due to the presence of additional beads.

Through this reward-based system, MENACE progressively refines its gameplay strategy. By reinforcing successful moves and discouraging less effective ones, MENACE becomes more adept at the game, increasing its chances of achieving victory or at least tie in future rounds.

Using modern-day reinforcement learning lingo, we would say that MENACE learns a policy. A policy refers to a mapping from the current environment observation to a probability distribution of the actions to be taken. In case of MENACE, the policy is determined by the number of beads of each color in a matchbox. We would calculate the probability of each action (each move) by taking the fraction of beads of a specific color in a matchbox over the total count of beads in that matchbox.

A Python implementation

In the remainder of this post, I’ll go over how I coded my own version of MENACE in Python. My implementation stays as close as possible to the original version as described by Donald Michie[1] but has the following additional features:

- My implementation doesn’t just model the game grids of the first player, but of the second player as well. This allows MENACE to play against itself.

- The number of beads to start out with in each turn is configurable.

- The number of beads that are used to punish and reward are configurable as well.

- You can visualize the state of all matchboxes before and after training.

- Some matchboxes may end up with 0 beads. In that case a random move is selected.

I’ll also show how to use my implementation for your own experiments.

Importing modules

Let’s start by importing the necessary modules.

from kaggle_environments import make, evaluate

from math import ceil

from IPython.display import HTML

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.animation as animation

import numpy as np

import random

import matplotlib

matplotlib.rcParams['animation.embed_limit'] = 2**128Loading environment lux_ai_s2 failed: No module named 'vec_noise'The matplotlib library is used to display the state of each matchbox. I import kaggle_environments so we can animate matches. Importing this last module outputs a warning but this can safely be ignored.

Helper functions

Game grids are represented using a simple string. Each string is 9 characters long and contains only X’s, O’s and .’s for empty squares. Donald Michie used O for the first player. I think most people start with X as does the kaggle_environment I imported. Maybe it’s a British thing as they call it noughts and crosses. It doesn’t matter much. I just decided to use X for the first player. I went with strings because this would allow me to use them as keys in a Python dictionary to look up the state of it’s corresponding matchbox.

For each game grid we need to be able to get a list of possible moves. The following function takes a string and returns a list of moves. It makes sure to remove any duplicate moves by rotating and mirroring the game grid and checking for equivalent moves.

def get_unique_moves(state):

moves = list(range(9))

unique_moves = [i for i, v in enumerate(state) if v == '.']

state_array = np.array(list(state)).reshape((3, 3)) # convert state to a 3x3 array

moves_array = np.array(moves).reshape((3, 3)) # convert moves to a 3x3 array

transformed_state_array = np.copy(state_array)

transformed_moves_array = np.copy(moves_array)

for _ in range(4):

transformed_state_array = np.rot90(transformed_state_array)

transformed_moves_array = np.rot90(transformed_moves_array)

transformed_moves = transformed_moves_array.flatten().tolist()

if np.array_equal(transformed_state_array, state_array):

for a, b in zip(moves, transformed_moves):

if a != b and a in unique_moves and b in unique_moves:

unique_moves.remove(b)

flipped_state_array = np.flipud(transformed_state_array)

flipped_moves_array = np.flipud(transformed_moves_array)

flipped_moves = flipped_moves_array.flatten().tolist()

if np.array_equal(flipped_state_array, state_array):

for a, b in zip(moves, flipped_moves):

if a != b and a in unique_moves and b in unique_moves:

unique_moves.remove(b)

return unique_movesCalling this function with an empty grid returns three moves: the center, a corner and a side.

print(get_unique_moves('.........'))[4, 7, 8]I’m just using index values to represent moves. Using color names would only complicate things.

Turn numbers start from 0.

def get_turn(state):

return 9 - state.count('.')The check_winner function returns X if the first player has won, O if the second player has won, or None if the game hasn’t finished yet, or has ended in a draw.

def check_winner(state):

winning_combinations = [

[0, 1, 2], [3, 4, 5], [6, 7, 8], # rows

[0, 3, 6], [1, 4, 7], [2, 5, 8], # columns

[0, 4, 8], [2, 4, 6] # diagonals

]

for combination in winning_combinations:

if state[combination[0]] == state[combination[1]] == state[combination[2]] != '.':

return state[combination[0]] # return the winning symbol (X or O)

return None # no winnerTo check if a game is actually over, we can call game_over.

def game_over(state):

return check_winner(state) or get_turn(state) == 9The get_current_player function returns who’s turn it is. If it returns None, then the game has already ended.

def get_current_player(state):

if game_over(state):

return None

if state.count('X') > state.count('O'):

return 'O'

return 'X'To make a move and get the next game grid we call update_game_state and pass the current game grid and a move.

def update_game_state(state, move):

return state[:move] + get_current_player(state) + state[move+1:]MENACE class

The MENACE class encapsulates the logic and functionality of MENACE, including initializing matchboxes, selecting moves, updating matchboxes based on game outcomes, and providing visualizations of the matchboxes.

class MENACE:

def __init__(self, initial_beads = [4,4,3,3,2,2,1,1,1], win_beads=3, lose_beads=-1, tie_beads=1):

self.matchboxes = {} # dictionary to store matchboxes and their beads

self.initial_beads = initial_beads

self.win_beads = win_beads

self.lose_beads = lose_beads

self.tie_beads = tie_beads

self.initialize_matchboxes()

def reset(self):

self.matchboxes = {}

self.initialize_matchboxes()

def initialize_matchboxes(self, state='.........'):

if game_over(state) or isinstance(self.get_move(state),int):

return

moves = get_unique_moves(state)

beads = [-1] * 9

for move in moves:

beads[move] = self.initial_beads[get_turn(state)]

self.matchboxes[state] = beads

for move in moves:

next_state = update_game_state(state, move)

self.initialize_matchboxes(next_state)

def _get_transformed_move(self, transformed_state_array, transformed_moves_array):

transformed_state = ''.join(transformed_state_array.flatten().tolist())

transformed_moves = transformed_moves_array.flatten().tolist()

if transformed_state in self.matchboxes:

beads = [0 if v < 0 else v for v in self.matchboxes[transformed_state]]

if sum(beads) == 0:

beads = [0 if v < 0 else 1 for v in self.matchboxes[transformed_state]]

return random.choices(transformed_moves, beads)[0]

return None

def get_move(self, state):

moves = list(range(9))

state_array = np.array(list(state)).reshape((3, 3)) # convert state to a 3x3 array

moves_array = np.array(moves).reshape((3, 3)) # convert moves to a 3x3 array

transformed_state_array = np.copy(state_array)

transformed_moves_array = np.copy(moves_array)

if isinstance(ret := self._get_transformed_move(transformed_state_array, transformed_moves_array), int):

return ret

for _ in range(4):

transformed_state_array = np.rot90(transformed_state_array)

transformed_moves_array = np.rot90(transformed_moves_array)

if isinstance(ret := self._get_transformed_move(transformed_state_array, transformed_moves_array), int):

return ret

flipped_state_array = np.flipud(transformed_state_array)

flipped_moves_array = np.flipud(transformed_moves_array)

if isinstance(ret := self._get_transformed_move(flipped_state_array, flipped_moves_array), int):

return ret

return None

def _update_transformed_move(self, transformed_state_array, transformed_moves_array, move, winner):

transformed_state = ''.join(transformed_state_array.flatten().tolist())

transformed_moves = transformed_moves_array.flatten().tolist()

if transformed_state in self.matchboxes:

beads = self.matchboxes[transformed_state]

if beads[transformed_moves.index(move)] > -1:

# update beads

if get_current_player(transformed_state) == winner:

beads[transformed_moves.index(move)] += self.win_beads

elif winner is None:

beads[transformed_moves.index(move)] += self.tie_beads

else:

beads[transformed_moves.index(move)] += self.lose_beads

if beads[transformed_moves.index(move)] < 0:

beads[transformed_moves.index(move)] = 0

return True

return False

def update_matchbox(self, state, move, winner):

moves = list(range(9))

state_array = np.array(list(state)).reshape((3, 3)) # convert state to a 3x3 array

moves_array = np.array(moves).reshape((3, 3)) # convert moves to a 3x3 array

transformed_state_array = np.copy(state_array)

transformed_moves_array = np.copy(moves_array)

if self._update_transformed_move(transformed_state_array, transformed_moves_array, move, winner):

return

for _ in range(4):

transformed_state_array = np.rot90(transformed_state_array)

transformed_moves_array = np.rot90(transformed_moves_array)

if self._update_transformed_move(transformed_state_array, transformed_moves_array, move, winner):

return

flipped_state_array = np.flipud(transformed_state_array)

flipped_moves_array = np.flipud(transformed_moves_array)

if self._update_transformed_move(flipped_state_array, flipped_moves_array, move, winner):

return

def plot_matchbox(self, state, ax):

beads = np.array(self.matchboxes[state]).reshape((3,3))

board = np.array(list(state)).reshape((3, 3))

ax.imshow(beads, cmap='Oranges', vmin=0)

ax.set_xticks([-0.5,0.5,1.5,2.5], labels='')

ax.set_yticks([-0.5,0.5,1.5,2.5], labels='')

ax.xaxis.set_ticks_position('none')

ax.yaxis.set_ticks_position('none')

ax.grid(True, color='black', linewidth=1)

for i in range(3):

for j in range(3):

if board[i, j] == 'X':

ax.plot([j-0.4,j+0.4],[i-0.4,i+0.4], color='black')

ax.plot([j+0.4,j-0.4],[i-0.4,i+0.4], color='black')

elif board[i, j] == 'O':

ax.add_artist(plt.Circle((j, i), 0.4, fill=False, color='black'))

elif beads[i, j] > -1:

ax.text(j, i, str(beads[i, j]), ha='center', va='center', color='white')

def plot_matchboxes(self, player='X'):

if player=='X':

cols = 16

states = sorted([k for k in self.matchboxes.keys() if get_turn(k) % 2 == 0 and get_turn(k) < 7], key=lambda v: get_turn(v))

rows = ceil(len(states) / cols)

fig, axs = plt.subplots(rows, cols, figsize=(cols,rows), gridspec_kw = {'wspace':0.1, 'hspace':0.1})

else:

cols = 17

states = sorted([k for k in self.matchboxes.keys() if get_turn(k) % 2 != 0], key=lambda v: get_turn(v))

rows = ceil(len(states) / cols)

fig, axs = plt.subplots(rows, cols, figsize=(cols,rows), gridspec_kw = {'wspace':0.1, 'hspace':0.1})

fig.subplots_adjust(top=0.96)

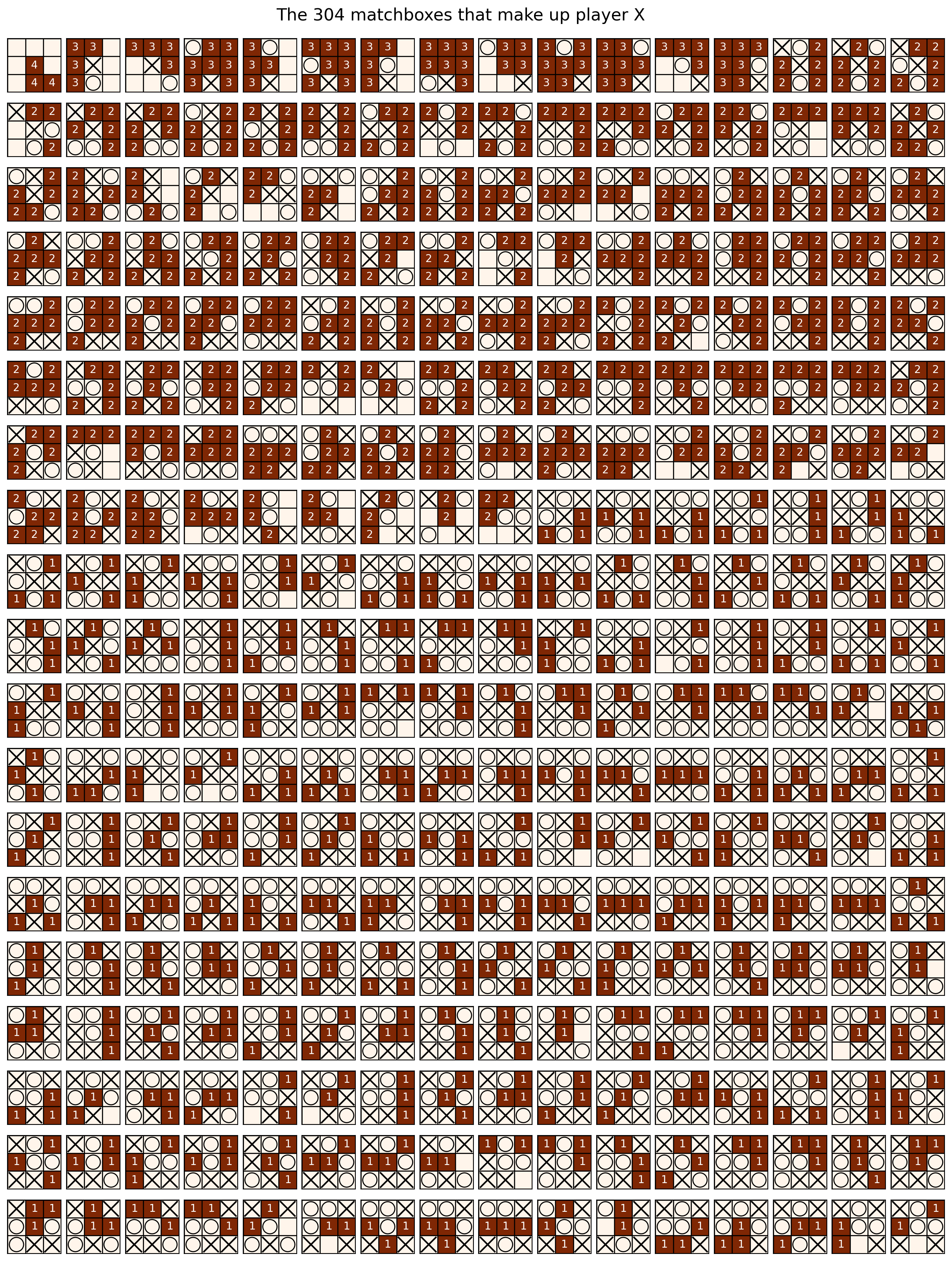

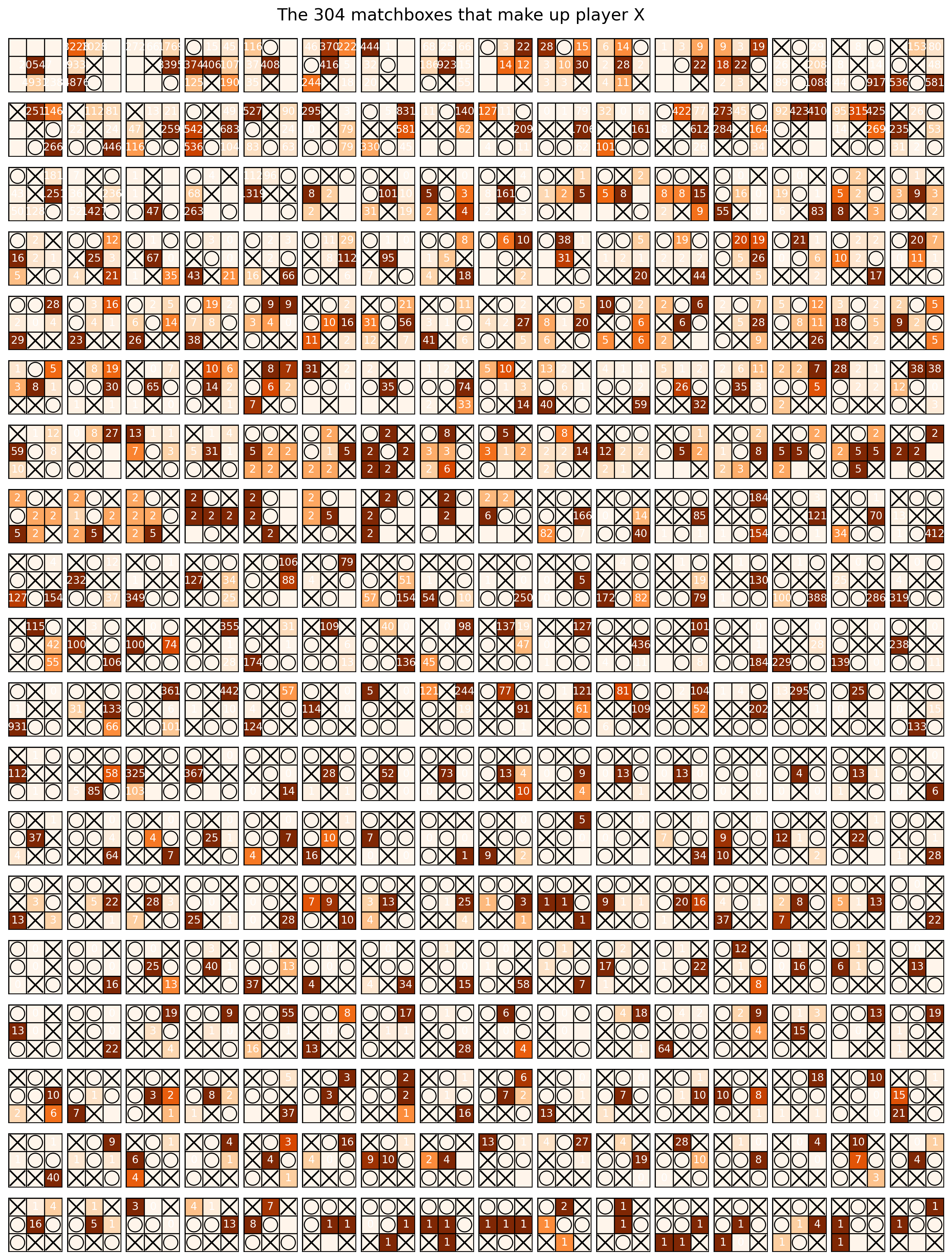

fig.suptitle(f"The {len(states)} matchboxes that make up player {player}", fontsize=16)

for r in range(rows):

for c in range(cols):

self.plot_matchbox(states[r*cols+c], axs[r, c])The class has an initialization method that takes in parameters such as the initial number of beads for each matchbox per turn, and the change in beads for a win, a loss, and a draw. It also sets up the matchboxes dictionary that is used to store the state for each matchbox as a list.

It calls the initialize_matchboxes method recursively creates and initializes matchboxes for all possible (but unique) grid configurations. It considers valid moves and assigns the corresponding number of beads based on the initial configuration parameters.

It might be interesting to experiment with the number of beads to add and remove after each win, loss, or draw. For now, we’ll just go with the defaults that were also used in the original MENACE and instantiate the class.

menace = MENACE()After all matchboxes are initialized we can visualize their state.

menace.plot_matchboxes('X')

plt.show()

Note how each game grid shows the number of beads corresponding to each move. Each game grid is actually a little heatmap where a darker orange means the move corresponding to that square is more likely to be selected. For now all grids have the same intensity. This will change once we start training MENACE.

As mentioned above, this Python implementation also includes all the matchboxes for the second player. You can visualize those by replacing the X by an O in the call to plot_matchboxes.

Training MENACE

We can train MENACE against itself or other agents. It makes sense to implement an agent as a function that takes in a game grid and returns a move.

We can easily define an agent that makes random moves.

# makes a random move

def random_agent(state):

return random.choice([i for i, v in enumerate(state) if v == '.'])Or we define an agent that moves in the first available empty square.

# move in the first available position

def first_agent(state):

return [i for i, v in enumerate(state) if v == '.'][0]We can use the following function that returns an agent that uses the menace object we instantiated above.

# returns an agent that get's a move from MENACE

def get_menace_agent(m):

def menace_agent(state):

return m.get_move(state)

return menace_agentThe following function takes in a MENACE object, and two agents and lets them play a game against each other. The function keeps track of which moves were made and after the game ends it calls the update_matchbox method in the MENACE object to update the number of beads.

def play_game(menace, agent1, agent2):

state = "........." # initial game state

moves = [] # list to store moves

players = [agent1, agent2]

for i in range(9):

move = players[i%2](state) # get move

moves.append((state, move)) # record the move

# update game state and check for a winner or draw

state = update_game_state(state, move)

if game_over(state):

break

winner = check_winner(state)

# update matchboxes based on the game outcome

for state, move in moves:

menace.update_matchbox(state, move, winner)

return winnerNote how this function calls update_matchbox for moves made by either agent. This gives us a lot of flexibility. For instance, we could invoke play_game with a MENACE instance and two random agents. The two random agents would play against each other and MENACE would be able to learn from their moves.

Training MENACE against a random player

For now, let’s have MENACE go first (agent1) and have it play against a random player (agent2). We let it play for 10000 rounds.

# Train MENACE

num_games = 10000 # number of games to play for training

game_results = []

agent1 = get_menace_agent(menace)

agent2 = random_agent

for i in range(num_games):

winner = play_game(menace, agent1, agent2)

game_results.append((i, winner))The outcome of each game is appended to the game_results list that we can use later to visualize how well it’s learning.

Let’s look at the state of each matchbox after these 10000 rounds.

menace.plot_matchboxes('X')

plt.show()

The following function creates an animation that shows the cumulative count for each outcome after each round.

def wins_and_ties_animation(game_results):

frames = 1000 if len(game_results) > 1000 else len(game_results)

step_size = 1 if len(game_results) <= 1000 else int(len(game_results) / 1000)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

max_y = max(

sum(1 for _, winner in game_results if winner == 'X'),

sum(1 for _, winner in game_results if winner == 'O'),

sum(1 for _, winner in game_results if winner is None)

)

def update(frame):

data = game_results[:(frame+1)*step_size]

cumulative_wins_X = sum(1 for _, winner in data if winner == 'X')

cumulative_wins_O = sum(1 for _, winner in data if winner == 'O')

cumulative_ties = sum(1 for _, winner in data if winner is None)

ax.clear()

ax.set_ylim(0, max_y)

ax.bar(['X', 'O', 'Ties'], [cumulative_wins_X, cumulative_wins_O, cumulative_ties])

ax.set_ylabel('Cumulative Wins')

ax.set_title('Cumulative Wins and Ties')

plt.close()

anim = animation.FuncAnimation(fig, update, frames=frames, interval=10)

return animLet’s see what it looks like for 10000 games of MENACE going first against a random player.

anim = wins_and_ties_animation(game_results)

HTML(anim.to_jshtml(default_mode='once'))